Why is my dog scared of people?

Many dog guardians feel overwhelmed, ashamed, or even frightened when their dog shows behaviours like growling, barking, lunging, or snapping at people. Whether it’s visitors, family members, children, or strangers, these behaviours can be deeply distressing and isolating.

But it’s important to understand: these actions are communication, not character flaws.

Your dog is not trying to dominate, embarrass, or betray you they’re trying to tell you something. And with the right knowledge and support, you can help them feel safer and more confident in the presence of people.

Dogs don’t actually want to vocalise or react as much as we might think. Barking, lunging, and growling are not their go-to choices they’re high-cost behaviours that expend a lot of energy and calories.

Dogs use them because they feel they have no better option in the moment. And it’s important to remember that we’ve bred dogs to live alongside us, to seek connection with people. So if a dog is reacting negatively to people, we need to ask why because something in their environment or past experience is disrupting that natural social bond. Their behaviour isn’t about disobedience or defiance it’s a signal that something needs to change & they are trying to tell us in the only way they know how.

What Is Aggression, Really?

Aggression is commonly defined as a set of behaviours used by animals, including dogs, to increase distance from a perceived threat. These behaviours can range from subtle signals like stiffening or staring, to more overt actions like growling, lunging, or biting. Importantly, aggression is not an emotional state or a personality trait it’s a communication strategy. Dogs display these behaviours when they feel uncomfortable, unsafe, or unable to escape a situation.

Many behaviour professionals prefer to use the term “distance-increasing behaviours” instead of “aggression.” This term shifts the focus away from moral judgement and toward function. It acknowledges that the dog is trying to create space, not cause harm. When we look at behaviour through this lens, we can better understand what the dog is experiencing and how to help them feel more secure.

In behavioural science, aggression isn’t a single emotion or diagnosis it’s a group of behaviours that dogs use when they feel they need to protect themselves or communicate discomfort. These behaviours include growling, snarling, barking, showing teeth, lunging, and biting. While they can be alarming to witness, they often occur because the dog feels afraid, overwhelmed, or threatened, and doesn’t have a better way to cope.

That’s why many professionals prefer the term “reactive behaviour” over “aggression.” As the dog is reacting to an internal or external stimuli.

It removes the stigma and focuses on the why behind the behaviour. When we ask, What is the dog reacting to, and why?, we open the door to understanding and to solutions that are kind, safe, and effective.

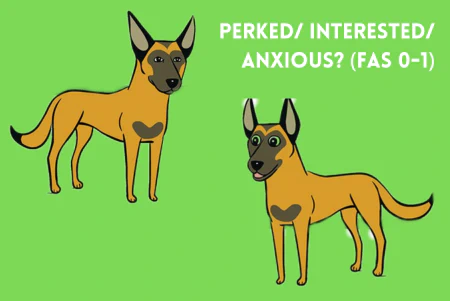

Canine FAS Scale

Common Causes of Reactive Behaviour Toward People

There are many underlying reasons a dog may show reactive behaviour toward humans. No two dogs are the same, and the context around their behaviour matters. Some of the most common causes include:

Fear or anxiety: Dogs who have had frightening experiences whether due to trauma, poor early socialisation, or unpredictable environments may see people as a potential threat. Their reactive behaviour in these moments is often their way of saying, “Please move away you’re a bit scary to me.”

Pain or medical issues: A dog who is injured or dealing with chronic pain may become reactive, especially when touched, approached suddenly, or handled in certain ways. This kind of reactivity can be their way of saying, “Please move away I’m not feeling great.”

Frustration or confusion: If a dog doesn’t understand what’s being asked of them or feels trapped, they may lash out as a way of expressing that discomfort. This behaviour may be their way of saying, “Please move away I feel trapped and confused.”

Resource guarding: Dogs may protect valued items such as toys, food, resting spots or even a specific person from perceived intrusions. This behaviour can be their way of saying, “Please move away I really need this item, it’s very important to me.”

Genetics or breed tendencies: Some dogs may have a genetic predisposition to heightened sensitivity, guarding, or protectiveness.

Understanding the root cause is essential because it guides how we help the dog and what kinds of support will be most effective.

It’s Not Your Fault

One of the most painful aspects of living with a reactive dog is the guilt and shame many guardians carry. I often see clients who are so embarrassed by their dog’s behaviour that they start to hide away, avoiding walks or visitors altogether. But here’s the truth: you’re not alone.

Studies show that around 76% of dogs will show some form of reactive behaviour in their lifetime.

That means most dog guardians have experienced this in some way. You have nothing to feel guilty about your dog’s behaviour is not a reflection of your love, care, or commitment. It’s a sign they need help, not that you’ve failed.

Reactive behaviour can develop even in dogs raised with compassion and consistency. Pain, trauma, fear, or even subtle environmental stressors can all play a role. Blame doesn’t help but understanding, support, and education do.

What You Can Do

Reacting with punishment shouting, leash corrections, or other aversives can make things worse. These responses increase stress, lower trust, and often suppress behaviour without solving the root problem. In behavioural science, punishment refers to anything that reduces the likelihood of a behaviour happening again.

- Positive punishment means adding something unpleasant after a behaviour for example, jerking the leash when a dog barks.

- Negative punishment means taking something away the dog wants for instance, ending a walk when the dog pulls.

While these methods can stop a behaviour in the moment, they often do so by increasing fear or confusion, which damages the relationship and doesn’t address the cause of the behaviour. Instead of teaching the dog what to do, punishment simply tells them what not to do often in a way that makes the original problem worse.

Instead, here’s how you can begin to make a real difference:

Book a veterinary check-up: This is a crucial first step. Pain and illness are common, hidden contributors to behaviour change. A veterinary exam is especially important if the behaviour appears suddenly, is sporadic with no clear pattern, or if resource guarding is involved. These signs may indicate discomfort, neurological changes, or other underlying health issues that should be addressed before behaviour modification work begins.

Keep a behaviour diary: Note what happened before, during, and after a reactive episode. Patterns can help you and a behaviourist identify triggers and plan changes.

Modify the environment: Can you give your dog more space? Use barriers, distance, or calm exits to reduce stress during visitor interactions.

Seek expert support: A Clinical Animal Behaviourist (CAB) can assess your dog’s behaviour holistically and provide a step-by-step, fear-free training plan tailored to your dog.

Be patient and consistent: Behaviour change takes time, especially when fear or past experiences are involved. Celebrate small wins and offer your dog a safe, predictable routine.

Support Starts With Understanding

Every behaviour is a message. When a dog reacts toward people, they’re not trying to make your life harder they’re trying to cope. Behaviour is both a form of medicine and communication it reflects your dog’s internal state and helps them manage their environment. Training and behaviour support are about influencing a dog’s emotional state how they feel about certain people, situations, or triggers in their world. By understanding what they’re telling us, we can start changing how they feel in those situations, and support them in a way that’s kind, practical, and effective.

Most dogs can learn to feel more at ease around people, as long as we understand what is causing the behaviour and apply the correct treatment. With kind, science-based training, many reactive dogs go on to live safe, happy lives with their families. There is hope.

And perhaps most importantly you deserve support too. Living with a reactive dog can feel isolating, but you are not alone. With the right tools and professional guidance, you and your dog can start moving forward together.

5 Things Every Guardian of a Reactive Dog Should Know

Is your dog struggling when left alone? You aren’t alone… 20% of dogs struggle with this…

Separation anxiety can be confusing, frustrating, and heartbreaking for both dogs and their humans. If you’re not sure what’s normal and what’s a red flag, my free guide, “5 Signs Your Dog May Be Struggling With Separation Anxiety” can help. It’s a quick, vet-trusted checklist that will help you recognise the early warning signs and understand what your dog might be trying to tell you.

Sign up below to get your copy and receive a gentle, supportive 6-part email series that walks you through how to help your dog feel calmer and more confident.

References

- Landsberg, G., Hunthausen, W. and Ackerman, L., 2013. Behavior problems of the dog and cat. 3rd ed. Saunders Elsevier.

- Overall, K.L., 2013. Manual of Clinical Behavioral Medicine for Dogs and Cats. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Horwitz, D.F. and Mills, D.S., 2009. BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Behavioural Medicine. 2nd ed. BSAVA.

- Moffat, K., 2008. Addressing canine aggression in veterinary practice. Veterinary Clinics: Small Animal Practice, 38(5), pp.983–1003.

- Mills, D.S., 2003. Medical paradigms for the study of problem behaviour: A critical review. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 81(3), pp.265–277.

- de Souza-Dantas, L.M., Döring, D. and Hohlbaum, K., 2017. Aggressive behaviour in dogs – a review of diagnosis and therapeutic approaches. Veterinary Record, 181(13), p.348.

- Haug, L.I., 2008. Canine aggression toward unfamiliar people and dogs. Veterinary Clinics: Small Animal Practice, 38(5), pp.1023–1041.

- Casey, R.A. et al., 2014. Human-directed aggression in domestic dogs (Canis familiaris): Occurrence in different contexts and risk factors. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 152, pp.52–63.